Pastorius's Latin: Challenges and Rewards of Transcription and Translation

by Dillon BrownAs an educator, lawyer, poet, and public official, Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651-1719) acquired a wide range of expertise over the course of his lifetime. In an effort to hand down his knowledge and advice, Pastorius wrote a Commonplace Book (commonly referred to as the Beehive manuscript) for his two sons between 1696 and 1719. Housed today in three volumes, the Beehive manuscript is an impressive collection of inscriptions, quotations, Biblical references, proverbs, and more.

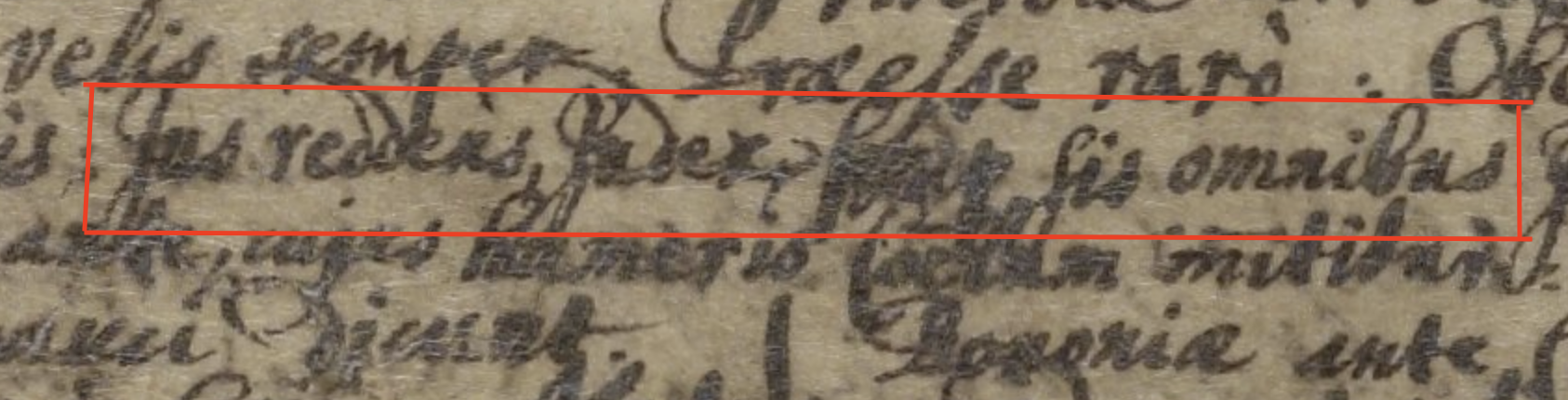

Transcribing an Early Modern manuscript such as Pastorius’s Beehive is a time consuming process that requires patience and a good eye. Written in small, cramped letters, this manuscript is nearly illegible in certain sections. Furthermore, in the Latin sections in particular, Pastorius’s handwriting is inconsistent with today’s linguistic conventions, thereby making transcription even more complicated. As in his English, his Latin letters “s” and “f” are taller than usual, extending below the line. For example, Pastorius writes “Ius reddens Iudex… fis omnibus.” At first glance, however, due to Pastorius’s handwriting, the reader may think that “fis” is actually “sis.”

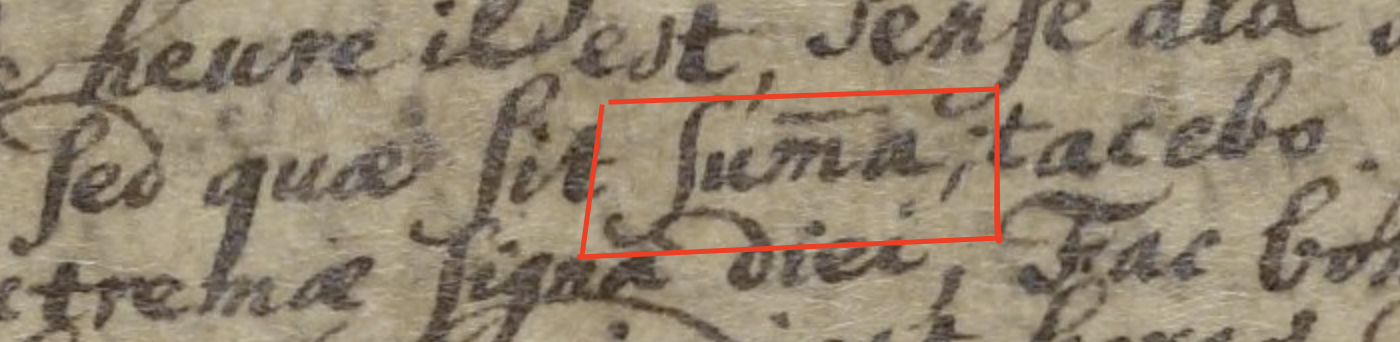

Although getting used to Pastorius’s script is challenging at first, greater ease comes with time. After spending a while with this manuscript, the reader will begin to recognize certain tricks and abbreviations that Pastorius invokes. For example, in numerous sentences, he writes “&c,” an abbreviation meaning “etc.” In addition, when writing in Latin, Pastorius puts other methods of truncation into effect. Firstly, Pastorius uses a technique that comes from German Kurrent script norms. In order to indicate that a singular letter should be a double one, he draws a line over it. Secondly, when Pastorius wants to add the Latin enclitic “-que,” he uses “q3” as shorthand.

Once the reader adapts to Pastorius’s way of writing, she may explore the manuscript and all of its cross-references and indices. However, as she dives deeper into the Commonplace Book, she will notice that Pastorius has incorporated words and sentences from a variety of languages including English, Latin, German, and French. These foreign languages pose a second difficulty: translation.

The accurate translation of this manuscript requires both persistence and focus. Particularly, throughout the manuscript’s Latin portions, the text is comprised of many long and confusing sentences. Thus, a translator of Pastorius’s Latin must toil to correctly identify the different parts of the sentences. In addition, occasionally, a subject or a verb is missing, and the translator must therefore consider what words to supply in order to make the sentence coherent. Not only does a translator of Pastorius’s Commonplace Book need to construct missing parts of sentences, but she must also be purposeful with how she decides to render each individual Latin word. Moreover, a translator must take into consideration the overarching context and the surrounding words in order to create a reasonable translation. For example, Pastorius writes, “Sicut umbra dies nostri.” Since this sentence does not contain a verb, the translator must provide one. Furthermore, the Latin word “umbra” can be translated in a variety of ways including “shadow,” “ghost,” and “shade.” Additionally, “umbra” is singular in form, but it makes more sense to translate it as plural so that it agrees with “dies nostri.” In this instance, the translator must realize that this section of the Beehive manuscript is focused on sundials and that its theme is the relationship between life and death. Thus, translating the sentence as “Our days are just like shadows” makes the most sense.

Additionally, as highlighted above, transcription mistakes are inevitable and common. In the example, if the transcriber were to mistake “fis” for “sis,” the translation would not make sense. Thus, a translator must also be on the lookout for trouble areas where she may have to deduce that a word or phrase was transcribed incorrectly.

The linguistic complexity of the Beehive manuscript renders it a rich and unique learning tool. In many aspects, the process of transcribing and translating Pastorius’s book is more important than the manuscript’s actual content. Transcription requires the reader to painstakingly examine each letter, character, space, and punctuation mark before even beginning to holistically analyze words and sentences. Then, translation challenges the reader to adapt her knowledge of a foreign language according to the era of the manuscript at hand. It forces her to slow down, to go back to the absolute fundamentals of the language, and to scrutinize each word’s case, number, gender, tense, voice, mood, and context. Unlike texts from more recent eras, Early Modern manuscripts incorporate archaic vocabulary, unique scripts, outdated grammatical constructions, and old-fashioned abbreviations. As a result, navigating an Early Modern manuscript may allow foreign language scholars to learn more about their language of study including its evolution. Despite the challenges that are involved, the process of analyzing manuscripts such as Pastorius’s Beehive is ultimately incredibly rewarding.