Substrate

« Binding | Substrate | Layout »

The substrate refers to the material or support on which the manuscript is written. One of the three p’s generally makes up the substrate in the Islamicate world: Papyrus, Parchment, Paper. Among those, paper is far and away the most common substrate, though parchment was also widely used during the early centuries of Islamic manuscript production.

Parchment

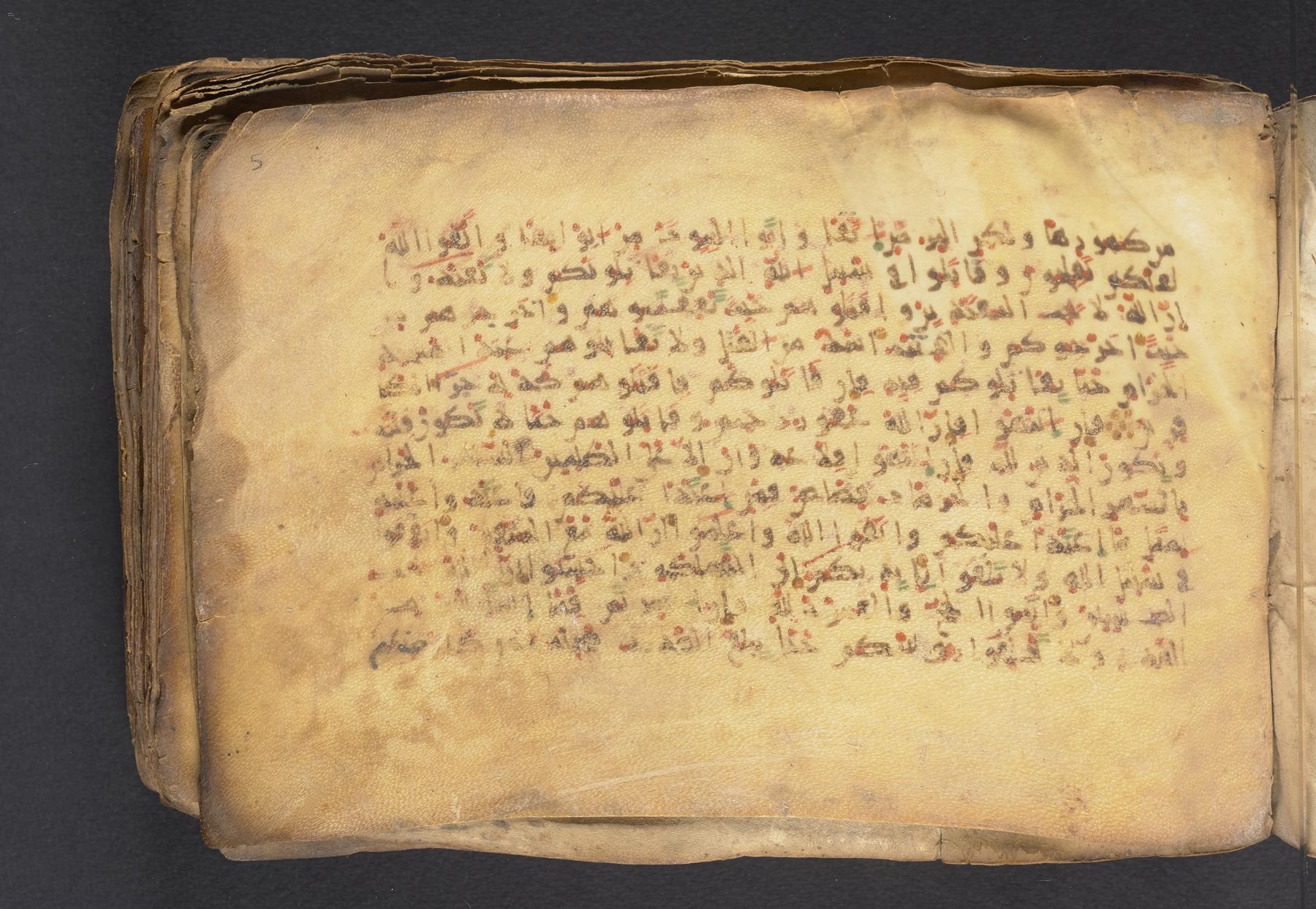

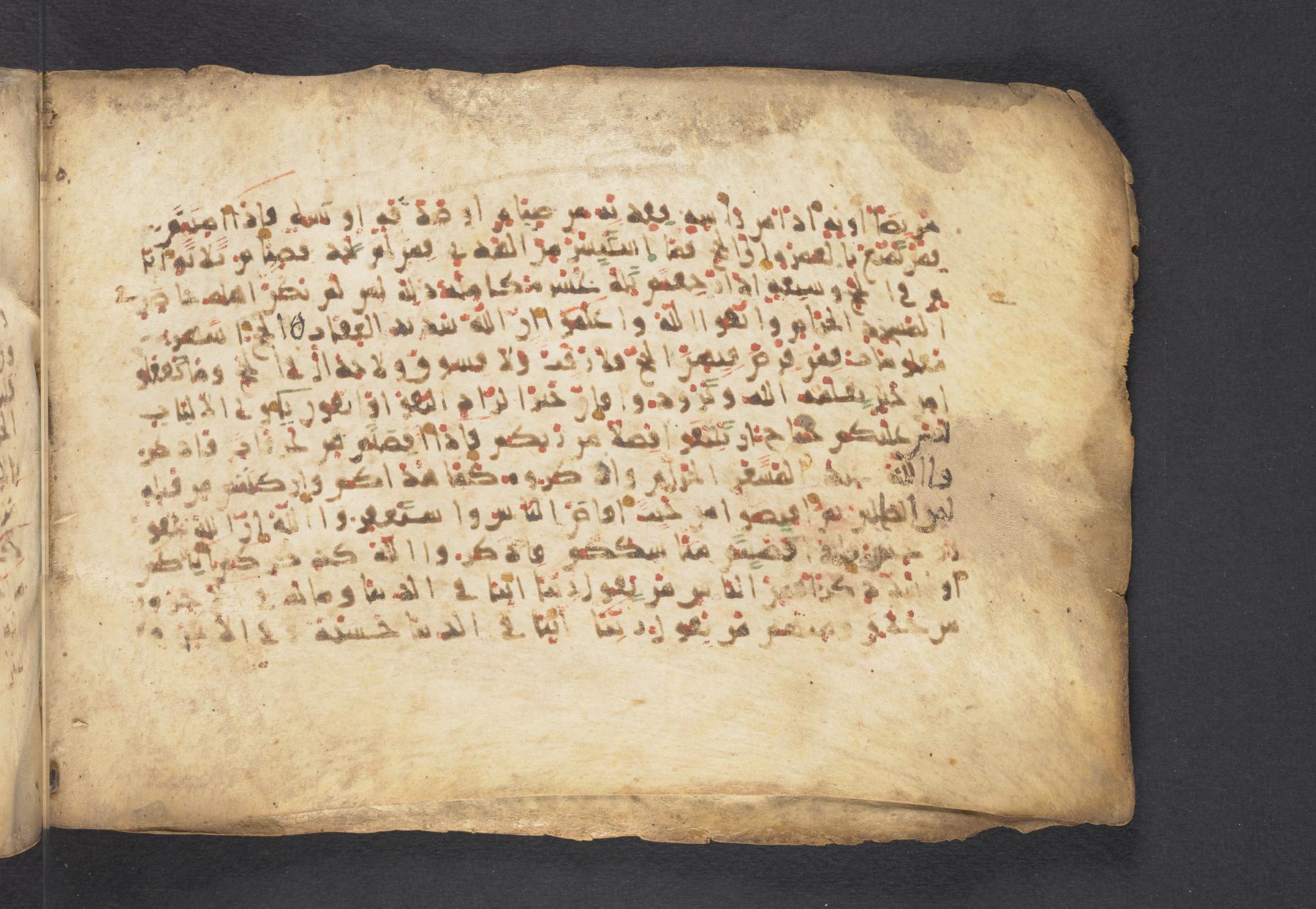

Parchment is labor-intensive and expensive to produce. Since parchment is animal skin (like leather), making parchment books requires many animals to be used. The skins need to be treated, scraped and stretched. When looking at parchment, the hair side and the flesh side are usually distinguishable. The hair side is normally darker (yellowish) and shows follicle marks and the flesh side is lighter and smoother. These photos are of a low quality parchment. You can see the differences in the hair side (top) and flesh side (bottom).

Parchment hair side (Image: Free Library of Philadelphia Lewis O 21 from OPenn)

Parchment hair side (Image: Free Library of Philadelphia Lewis O 21 from OPenn)

Parchment flesh side (Image: Free Library of Philadelphia Lewis O 21 from OPenn)

Parchment flesh side (Image: Free Library of Philadelphia Lewis O 21 from OPenn)

Because of the time, expense, and the necessary availability of animals for producing parchment, it pretty quickly went out of use once the knowledge of how to make paper spread to the Islamic world in the 8th century.

Paper

In simplest terms, paper is made of plant fiber, most often once it has been woven into cloth. The cloth is broken down again into its fibers, called pulp, and mixed with water and sometimes another ingredient which helps keep the paper from absorbing liquids once it is dried. A paper mold is lowered into the vat of fibers suspended in water and raised again flat so that the extra water runs off the sides and you are left with a thin layer of fibers over a grid (the mold). The paper is then dried and polished before it can be used. Because of this mold on which paper is made, when you hold paper up to light and look through it, you can see patterns left over from the mold.

In the Islamic world, paper comes in three general types:

- wove,

- visible laid lines only and

- visible laid and chain lines.

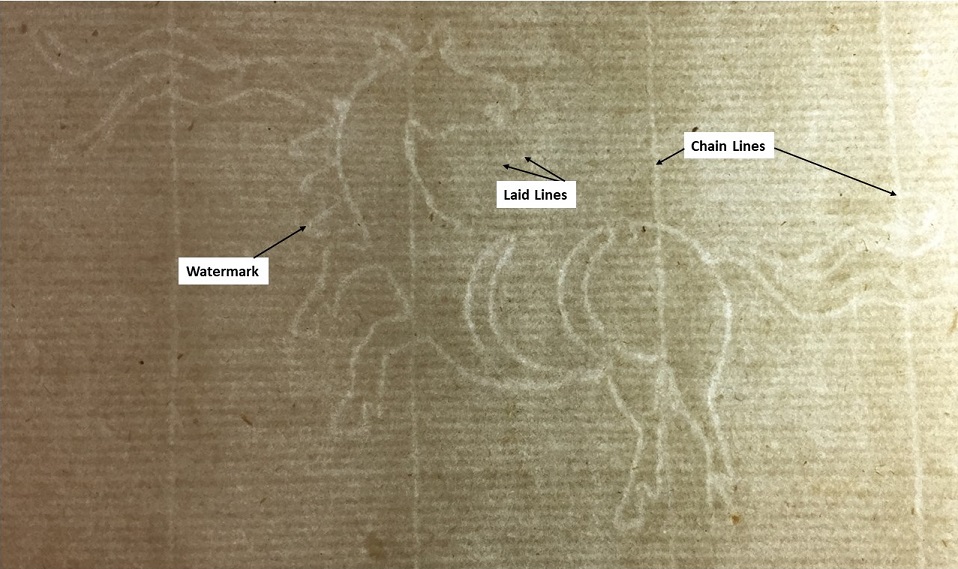

This refers to what you see when you hold a leaf of paper up to light. Handmade papers generally have some sort of pattern you can see, the exception is wove paper which has no pattern. Other papers generally have chain lines (wider spaced lines) and laid lines, also called water lines (narrowly spaced lines). These lines are a result of the mold on which the paper is made. You can also sometimes see writing or drawings in the paper itself which are called watermarks. Watermarks are most often found on imported European papers and not on papers produced in the Islamic world. This photo with labels shows a detail of laid and chain lines and a watermark of a horse.

(Image: Kelly Tuttle from Upenn Libraries Ms. Codex 1951)

(Image: Kelly Tuttle from Upenn Libraries Ms. Codex 1951)

Indo-Persian handmade paper generally has laid lines only, so only the closely-spaced lines. This type of paper was made on a reed or grass mold and was used all over the Eastern portion of the Islamic world (Iran, India and surrounding areas) even up to the 20th century. For a manuscript showing the process of papermaking in the Indo-Persian world and a description with modern pictures of how it is done, see the British Library’s post about a papermaking workshop they held.

Syro-Egyptian handmade paper tends to have chain lines in groups of two or three. As you can see in the photo below, they are running parallel to the text. This type of paper was used in the Islamic world in the central region (Egypt, Syria and surrounding areas) until the mid-15th century when it was replaced by European paper.

(Image: Kelly Tuttle from the Katz Center, CAJS Rar Ms 123)

(Image: Kelly Tuttle from the Katz Center, CAJS Rar Ms 123)

In the mid-15th century, European paper, started to be exported to the Islamic world first from Italy and then from other Western European countries. For manuscript production in the Islamic world, it was often cheaper to import paper than it was to make it locally. Generally, European paper has evenly spaced chain lines and laid lines. It also often has watermarks, like what can be seen in the illustration below.

Watermarks on made-for-export European paper often involved crescent moons of some kind. A popular type of paper, 17th century and after, was known as trelune for the three crescent moon watermark.

(Image: Kelly Tuttle)

Structure

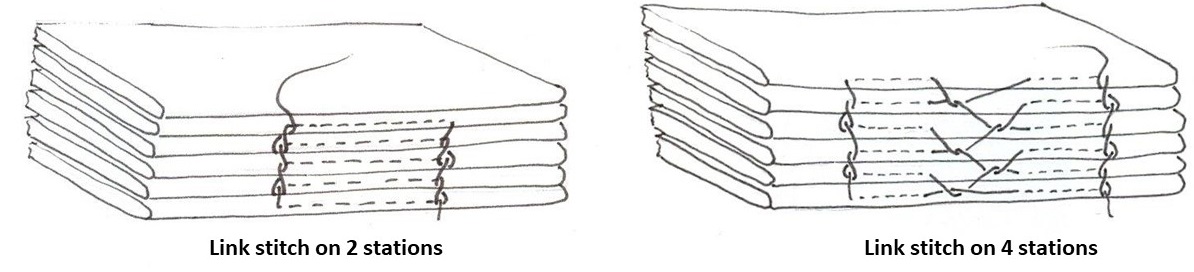

Codices (manuscript books) are made up of stacks of folded sheets or leaves, called folios. Each folio has two pages: the front side is called the recto or “a” side, and the back is the verso or “b” side. These stacks are called quires or gatherings and consist of groups of leaves or folios folded in half to form bifolia (singular: bifolium). The quires are then placed one on top of the other and sewn together through two or four stitching stations. See the images below from Karin Scheper and Paul Hepworth’s site, Islamic Manuscript Conservation to help you visualize how the quires are sewn.

(Images from: Karin Scheper, “Structure” on Islamic Manuscript Conservation Terminology (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0)

(Images from: Karin Scheper, “Structure” on Islamic Manuscript Conservation Terminology (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0)

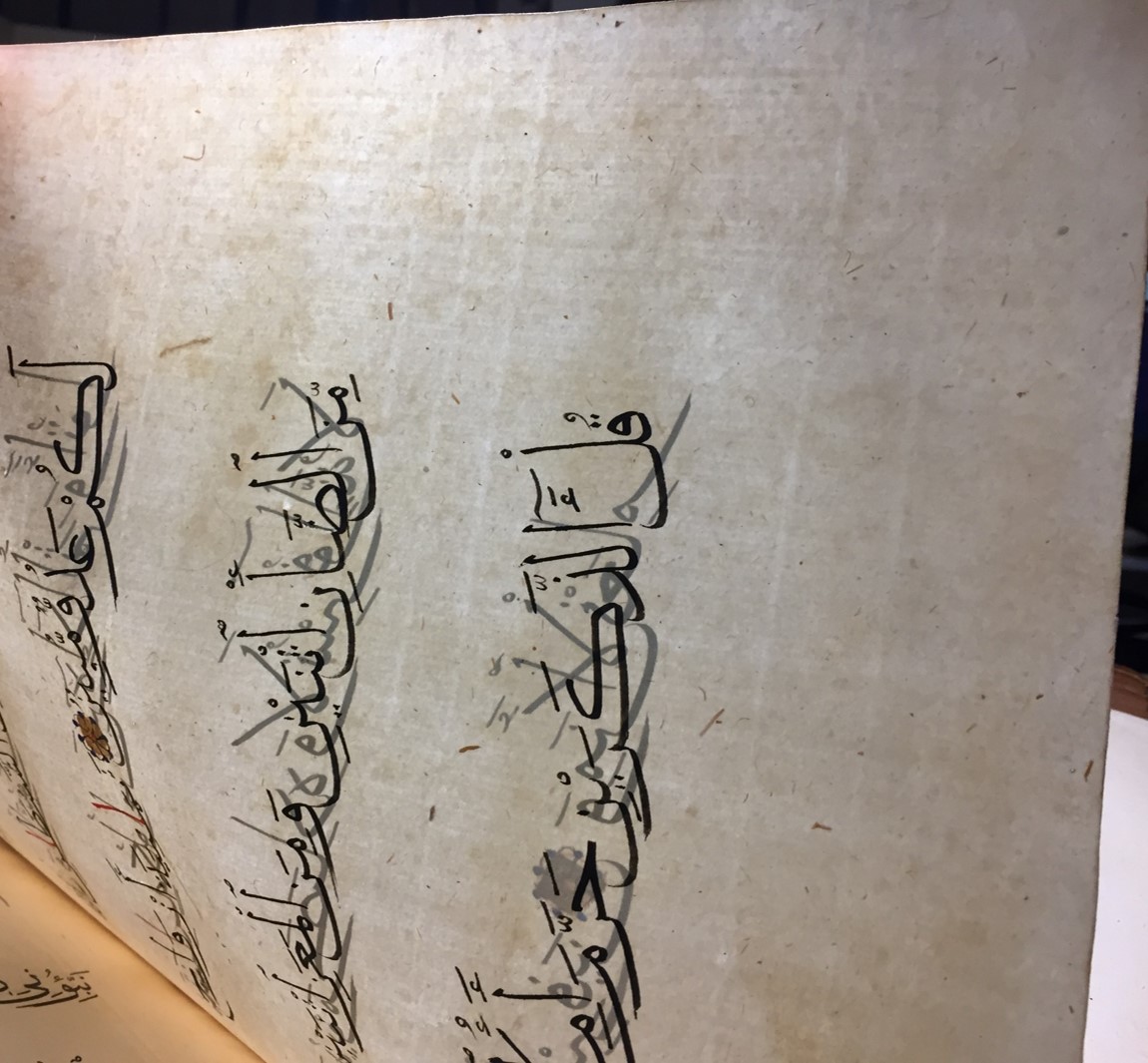

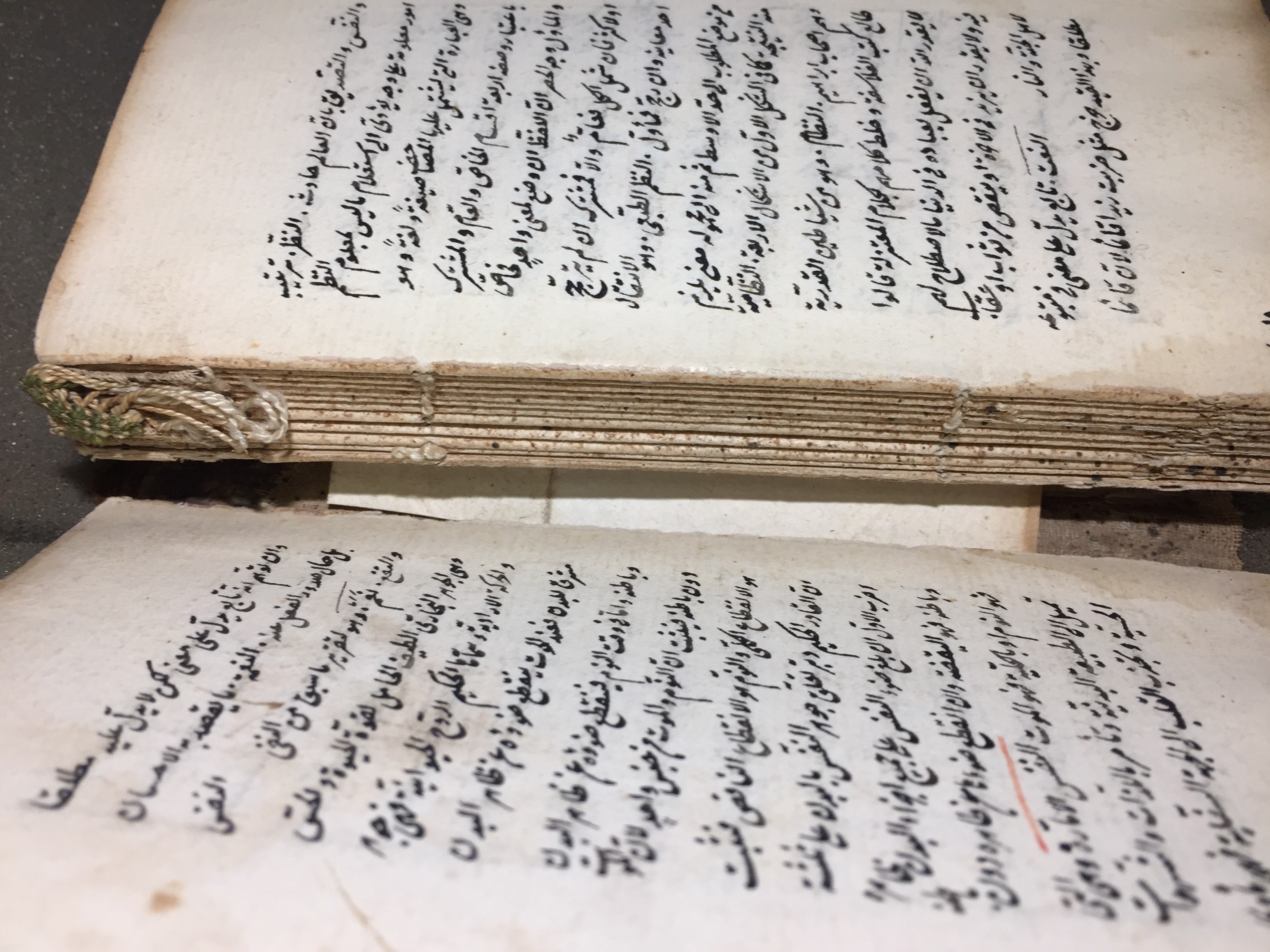

Here’s a side view of a stack of quires. As you can see, there are two sewing stations, but the threads used for both stations have broken or come apart over time so that the quires no longer are attached together and slip around when the manuscript is open.

(Image: Kelly Tuttle)

(Image: Kelly Tuttle)

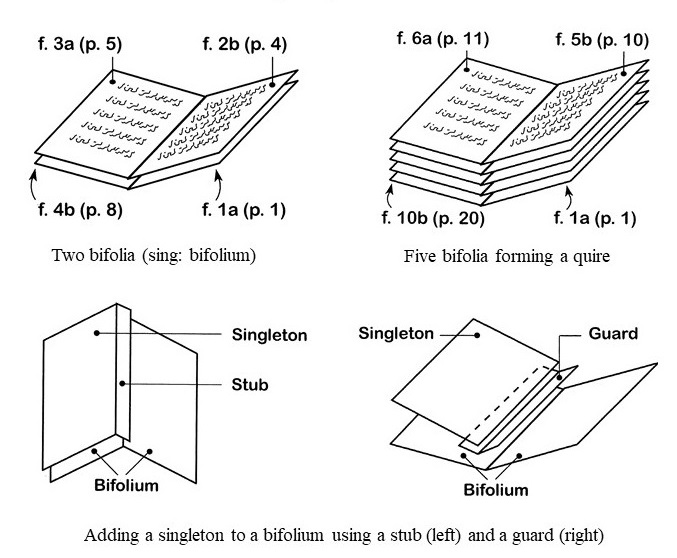

When looking at a quire, it is common to find 5 bifolia in each one, which means 10 leaves and 20 pages. The illustrations below from Adam Gacek’s Arabic Manuscripts may help you visualize this. The illustrations also show how a single leaf (singleton) can be added to a bifolium to make a set of three leaves. In the top set of illustrations, “f.” stands for folio, meaning half of a folded leaf, and “p.” stands for page, meaning one side of a folio.

(Images from: Adam Gacek (2009) Arabic Manuscripts, pp. 107, 210-11, 248)

(Images from: Adam Gacek (2009) Arabic Manuscripts, pp. 107, 210-11, 248)

Collation, that is, figuring out and describing the number of leaves in a quire and how many quires are in a codex can be quite difficult depending on whether single leaves have been added or removed, whether each quire has the same number of leaves, and how tight the binding is. It is often helpful to look for the sewing (thread) on the inside of a quire to find the middle of that quire. Then you can count from middle to middle to try to determine the number of leaves in a quire.

That concludes the introduction to substrate and structure. You can do the Substrate exercise now, or jump to any other page you like.

You can also go check out the References, other SIMS Resources or look at the Glossary for more photos.